The problem is finding a vector that pays for itself as you scale.

We see a problem and we think we've "solved" it, but if there isn't a scalable go-to-market business approach behind the solution, it's not going to work.

This is where engineers and other problem solvers so often get stuck. Industries and organizations and systems aren't broken because no one knows how to solve their problem. They're broken because the difficult part is finding a scalable, profitable way to market and sell the solution.

Take textbooks, for example. The challenge here isn't that you and I can't come up with a far better, cheaper, faster and more fair way to produce and sell and use textbooks. The problem is that the people who have to approve, review and purchase textbooks are difficult to reach, time-consuming to educate and expensive to sell.

Or consider solar lanterns as a replacement for kerosene. They are safer, cheaper and far healthier. But that's not the problem. The problem is building a marketing and distribution network that permits you to rapidly educate a billion people as to why they want to buy one at a price that would permit you to make them in quantity.

Sure, you need a solution to the problem. But mostly what you need is a self-funding method to scale your solution, a way of interacting with the market that gains in strength over time so you can start small and get big, solving the problem as you go.

May 8, 2012

When people say, "The tipping point," they often misunderstand the concept in Malcolm's book. They're actually talking about the flipping point.

The tipping point is the sum total of many individuals buzzing about something. But for an individual to start buzzing, something has to change in that person's mind. Something flips from boredom or ignorance to excitement or anger.

It starts when the story of a brand or a person or a store or an experience flips in your head and it goes from good to bad, or from ignored to beloved. The flipping point doesn't represent the sum of public conversations, it's the outcome of an activated internal conversation.

It's easy to wish and hope for your project to tip, for it to magically become the hot thing. But that won't happen if you can't seduce and entrance an individual and then another.

Before the tipping point, someone has to flip. And then someone else. And then a hundred more someones.

We resist incremental improvement in our offerings and our stories because it just doesn't seem likely that one good interaction or one tiny alteration can possibly lead to a significant amount of flipping. And we're right—it won't. The flipping point (for an individual) is almost always achieved after a consistent series of almost invisible actions that create a brand new whole.

And the reason it's so difficult? Because you're operating on faith. You need to invest and apparently overinvest (time and money and effort) until you see the results. And most of your competition (lucky for you) give up long before they reach the point where it pays off.

May 7, 2012

At the local gym, it's not unusual to see hardcore members contorting themselves to fool the stairmaster machine into giving them good numbers. If you use your arms, you can lift yourself off the machine and trick it into thinking you're working yourself really hard.

Of course, you end up with cramped shoulders and a lousy workout, but who cares, the machine said you burned 600 calories…

The same thing happens with authors who put themselves and their readers through the wringer to get a spot on the New York Times Bestseller list (more on this here). Danielle LaPorte built a huge campaign around putting her book on the list, she succeeded in selling a huge number of hardcover copies in a week (far more than most other books) but didn't make the list because of a secret editorial decision that she's not privy to. At the same time, other authors who do a better job of decoding the secrets end up on the list with far fewer sold.

The point isn't that the list is crooked and unfair (though it is). It measures how good you are at getting on the list, not how many copies of the book your readers buy. The reason to avoid the false metric is that it messes with your shoulders, with the way you approach the work, with the real reason you did the project in the first place.

A third example: many car brands now go to obsessive lengths to contact recent car buyers and ask them to rate their buying experience on a scale of one to five. They use these rankings to allocate cars to dealers, ostensibly to reward the good dealerships. Of course, the dealers are in on the game, and instead of doing the intended thing–providing a great experience–all they do is work hard to get people to give them a five when a drone in a call center makes the call. Many of them will clearly state to a customer, "If anything has happened today that would prevent you from giving us a five when they call, please tell us right now…"

The system of false metrics doesn't create a better buying experience, it creates a threatened customer with pressure to give a five.

And my last example: The Arbitron radio rating system used to rely on diaries in which it asked radio listeners to write down which station they had listened to during the day. Several consultants came along with a service that they guaranteed would raise the ratings of any station that hired them. The secret? Repeat the station's call letters twice as often. It turned out that more repetition led to better recall, which led to more people writing down the call letters which led to 'better' ratings.

A useful metric is both accurate (in that it measures what it says it measures) and aligned with your goals. Making your numbers go up (any numbers–your bmi, your blood sugar, your customer service ratings) is pointless if the numbers aren't related to why you went to work this morning.

May 6, 2012

Mothers with daughters adore this bestselling book by Sarah Kay. It's a little piece of magic.

I published it because every time I saw the video, it made me cry. But you can't give your mom a video link for Mother's Day, can you?

Check out these reviews:

"Give this lovely little book to any parent in your life who is trying to instill the values of self-love, adventurousness and intelligent defiance in their children.

Give this book to any parent who questions themselves all too often, even when they are one of the best parents you know.

Give this book to any parent who needs a little reassurance that their love is more than enough."

"I highly recommend this book for new moms, old moms, one day want to be moms, or to anyone that needs to be reminded that they're loved. "

"I bought six copies of this book, keeping one and giving the remaining five to my mom, my aunt, and some dear friends (and mothers)"

"I found this book and decided to purchase 2 copies: one for my daughter and one for myself. It is wonderful and well worth buying for gifts."

"This is a precious gift to share if you are a daughter or have a daughter of any age."

"Some books should still be in print for years to come and this is one of them. Great gift idea! "

May 5, 2012

Care.

Care more than you need to, more often than expected, more completely than the other guy.

No one reports liking Steve Jobs very much, yet he was as embraced as any businessperson since Walt Disney. Because he cared. He cared deeply about what he was making and how it would be used. Of course, he didn't just care in a general, amorphous, whiny way, he cared and then actually delivered.

Politicians are held in astonishingly low esteem. Congress in particular is setting record lows, but it's an endemic problem. The reason? They consistently act as if they don't care. They don't care about their peers, certainly, and by their actions, apparently, they don't care about us. Money first.

Many salespeople face a similar problem–perhaps because for years they've used a shallow version of caring as a marketing technique to boost their commissions. One report by the National Association of Realtors found that more than 90% of all homeowners are never again contacted by their real estate agent after the contracts for the home are signed. Why bother… there's no money in it, just the possibility of complaints. Well, the reason is obvious–you'd come by with cookies and intros to the neighbors if you cared.

Economists tell us that the reason to care is that it increases customer retention, profitability and brand value. For me, though, that's beside the point (and even counter to the real goal). Caring gives you a compass, a direction to head and most of all, a reason to do the work you do in the first place.

Care More.

It's only two words, but it's hard to think of a better mantra for the organization that is smart enough to understand the core underpinning of their business, as well as one in search of a reason for being. No need to get all tied up in subcycles of this leads to this which leads to that so therefore I care… Instead, there's the opportunity to follow the direct and difficult road of someone who truly cares about what's being made and who it is for.

There are two common mistakes here:

Frequently reconsidering decisions that ought to be left alone. Once you enroll in college, it is both painful and a waste to spend the first five minutes of every morning wondering if you should drop out or not. Once you've established a marketing plan, it doesn't pay to reevaluate it every time your shop is empty. And once you've committed to a partnership, it's silly to reconsider that choice every time you have a disagreement.

In addition to wasting time, the frequent reconsideration sabotages the effort your subconscious is trying to make in finding ways to make the current plan work. Spending that creative energy wondering about the plan merely subtracts from the passion you could put into making it succeed.

On the other hand, particularly in organizations, failure to reconsider long-held decisions is just as wasteful. Should you really be in that business? Should this person still be working here? Is that really the best policy?

Jay Levinson used to say that you should keep your ad campaign even after your best customers, your wife and your partner get bored with it. Change it when the accountant says it's time. And Zig Ziglar likes to talk about the pilot on his way from New York to Dallas. Wind blows the plane off course after a few minutes. The right thing to do is adjust the course and head on. The wrong thing to do is head back to New York and start over (or to reconsider flying to Dallas at all).

May 4, 2012

If you have a list of 1000 subscribers or 5,000 fans or 10,000 supporters, you have a choice to make.

You can create stories and options and benefits that naturally spread from this group to their friends, and your core group can multiply, with 5,000 growing to 10,000 and then 100,000.

Or you can put the group through a sales funnel, weed out the free riders and monetize the rest. A 5% conversion rate means you just turned 5,000 interested people into 250 paying customers.

Multiplying scales. Dividing helps you make this quarter's numbers.

May 3, 2012

Often, our instinct is to make the current bump in the road far more urgent than it actually is. It focuses our attention and rallies those around us to take immediate and deliberate action.

After all, if this is the big one, of course we should drop everything and deal with it.

Missing from this equation is the cost of dropping everything. The short-term herk and jerk that is delivered by an organization that responds to those that amplify problems into catastrophes inevitably leads to poor performance in the long run.

Employees who do this ought to be counseled to cut it out. It's not what we hired you to do. Bosses who catastrophize are often hesitant to admit it, though, and if you work for one, it's going to continually hurt your ability to do your best work.

And non-profits who catastrophize to meet their next funding goal inevitably sabotage the very work they set it out to do in the first place, all because it's an easy way to raise some extra money.

May 2, 2012

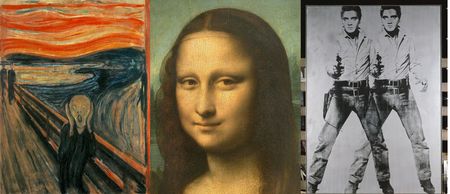

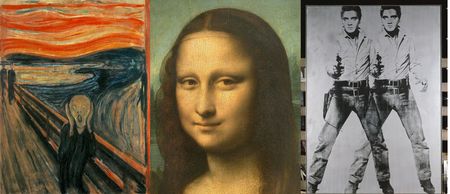

The fine art market continues to generate headline-making sales. This year, paintings by Warhol and Munch are expected to sell for more than $50 million each.

What makes a painting famous enough to sell for that much money?

Consider the Mona Lisa. The reason that it's the most famous (and arguably the most valuable) painting in the world is that it was stolen in 1911. (Even Pablo Picasso was questioned as a possible suspect). For two years, it was a media sensation–precisely when newspapers were coming into their own. For two years it was front page news. As the world media-ized itself, we needed an icon to stand for "famous painting" and the Mona Lisa was it.

Media cycles have gotten shorter and shorter since then, and ironically, it was Andy himself who predicted that one day we'd all be famous for fifteen minutes. The thing is, being famous for fifteen minutes isn't sufficient to make your painting worth $80 million.

Andy never had his own tv show, wouldn't have had the most viral video on YouTube and wasn't focused on the fast pump of fame. It turns out that get big fast (and then fade) doesn't build a reputation that pays.

Media volatility makes more people and more ideas famous for ever shorter periods of time. What the fine art market shows us, though, is that real value isn't created by this volatile fame. Consistently showing up on the radar of the right audience is more highly prized than reaching the masses, once then done. This works for every career, even if you've never touched a brush.

May 1, 2012